Molly’s Cabin in The Globe and Mail Aug. 2009

Molly’s Cabin in Globe and Mail: Carolyn Ireland

Carolyn Ireland—In the best Georgian Bay tradition, long-time cottagers are fiercely protective of their secluded chunk of rock. They face down furious storms, dive unflinchingly into chilly water and maintain a rather casual relationship with bathing suits.

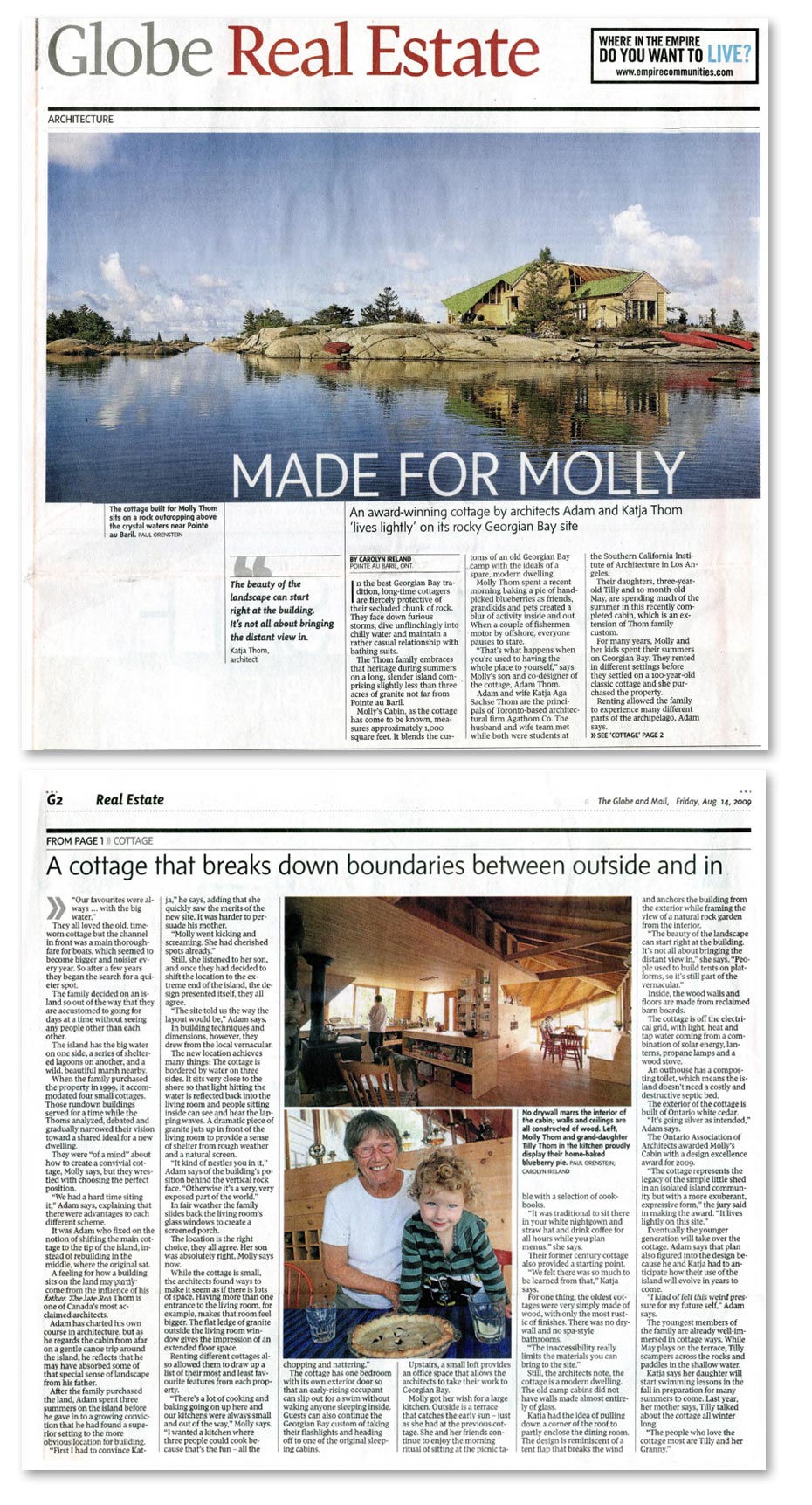

The Thom family embraces that heritage during summers on a long, slender island comprising slightly less than three acres of granite not far from Pointe au Baril. Molly’s Cabin, as the cottage has come to be known, measures approximately 1,000 square feet. It blends the customs of an old Georgian Bay camp with the ideals of a spare, modern dwelling.

Molly Thom spent a recent morning baking a pie of hand-picked blueberries as friends, grandkids and pets created a blur of activity inside and out. When a couple of fishermen motor by offshore, everyone pauses to stare. “That’s what happens when you’re used to having the whole place to yourself,” says Molly’s son and co-designer of the cottage, Adam Thom.

Adam and wife Katja Aga Sachse Thom are the principals of Toronto-based architectural firm Agathom Co. The husband and wife team met while both were students at the Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles. Their daughters, three-year-old Tilly and 10-month-old May, are spending much of the summer in this recently completed cabin, which is an extension of Thom family custom. For many years, Molly and her kids spent their summers on Georgian Bay. They rented in different settings before they settled on a 100-year-old classic cottage and she purchased the property. Renting allowed the family to experience many different parts of the archipelago, Adam says.

“Our favourites were always … with the big water.” They all loved the old, timeworn cottage but the channel in front was a main thoroughfare for boats, which seemed to become bigger and noisier every year. So after a few years they began the search for a quieter spot. The family decided on an island so out of the way that they are accustomed to going for days at a time without seeing any people other than each other.

The island has the big water on one side, a series of sheltered lagoons on another, and a wild, beautiful marsh nearby. When the family purchased the property in 1999, it accommodated four small cottages. Those rundown buildings served for a time while the Thoms analyzed, debated and gradually narrowed their vision toward a shared ideal for a new dwelling.

They were “of a mind” about how to create a convivial cottage, Molly says, but they wrestled with choosing the perfect position. “We had a hard time siting it,” Adam says, explaining that there were advantages to each different scheme. It was Adam who fixed on the notion of shifting the main cottage to the tip of the island, instead of rebuilding in the middle, where the original sat.

A feeling for how a building sits on the land may partly come from the influence of his father. The late Ron Thom is one of Canada’s most acclaimed architects. Adam has charted his own course in architecture, but as he regards the cabin from afar on a gentle canoe trip around the island, he reflects that he may have absorbed some of that special sense of landscape from his father.

After the family purchased the land, Adam spent three summers on the island before he gave in to a growing conviction that he had found a superior setting to the more obvious location for building. “First I had to convince Katja,” he says, adding that she quickly saw the merits of the new site. It was harder to persuade his mother. “Molly went kicking and screaming. She had cherished spots already.” Still, she listened to her son, and once they had decided to shift the location to the extreme end of the island, the design presented itself, they all agree.

“The site told us the way the layout would be,” Adam says. In building techniques and dimensions, however, they drew from the local vernacular. The new location achieves many things: The cottage is bordered by water on three sides. lt sits very close to the shore so that light hitting the water is reflected back into the living room and people sitting inside can see and hear the lapping waves. A dramatic piece of granite juts up in front of the living room to provide a sense of shelter from rough weather and a natural screen.

“It kind of nestles you in it,” Adam says of the building’s position behind the vertical rock face. “Otherwise it’s a very, very exposed part of the world.” In fair weather the family slides back the living room’s glass windows to create a screened porch. The location is the right choice, they all agree. Her son was absolutely right, Molly says now.

While the cottage is small, the architects found ways to make it seem as if there is lots of space. Having more than one entrance to the living room, for example, makes that room feel bigger. The flat ledge of granite outside the living room window gives the impression of an extended floor space. Renting different cottages also allowed them to draw up a list of their most and least favourite features from each property. “There’s a lot of cooking and baking going on up here and our kitchens were always small and out of the way,” Molly says. “I wanted a kitchen where three people could cook because that’s the fun—all the chopping and nattering.”

The cottage has one bedroom with its own exterior door so that an early-rising occupant can slip out for a swim without waking anyone sleeping inside. Guests can also continue the Georgian Bay custom of taking their flashlights and heading off to one of the original sleeping cabins. Upstairs, a small loft provides an office space that allows the architects to take their work to Georgian Bay.

Molly got her wish for a large kitchen. Outside is a terrace that catches the early sun—just as she had at the previous cottage. She and her friends continue to enjoy the morning ritual of sitting at the picnic table with a selection of cookbooks. “It was traditional to sit there in your white nightgown and straw hat and drink coffee for all hours while you plan menus,” she says. Their former century cottage also provided a starting point.

“We felt there was so much to be learned from that,” Katja says. For one thing, the oldest cottages were very simply made of wood, with only the most rustic of finishes. There was no drywall and no spa-style bathrooms. “The inaccessibility really limits the materials you can bring to the site.” Still, the architects note, the cottage is a modern dwelling. The old camp cabins did not have walls made almost entirely of glass.

Katja had the idea of pulling down a corner of the roof to partIy enclose the dining room. The design is reminiscent of a tent flap that breaks the wind and anchors the building from the exterior while framing the view of a natural rock garden from the interior. “The beauty of the landscape can start right at the building. It’s not all about bringing the distant view in,” she says. “People used to build tents on platforms, so it’s still part of the vernacular.” Inside, the wood walls and floors are made from reclaimed barn boards.

The cottage is off the electrical grid, with light, heat and tap water coming from a combination of solar energy, lanterns, propane lamps and a wood stove. An outhouse has a composting toilet, which means the island doesn’t need a costly and destructive septic bed. The exterior of the cottage is built of Ontario white cedar. “It’s going silver as intended,” Adam says.

The Ontario Association of Architects awarded Molly’s Cabin with a design excellence award for 2009. “The cottage represents the legacy of the simple little shed in an isolated island community but with a more exuberant, expressive form,” the jury said in making the award. “It lives lightly on this site.”

Eventually the younger generation will take over the cottage. Adam says that plan also figured into the design because he and Katja had to anticipate how their use of the island will evolve in years to come. “I kind of felt this weird pressure for my future self,” Adam says. The youngest members of the family are already well-immersed in cottage ways. While May plays on the terrace, Tilly scampers across the rocks and paddles in the shallow water. Katja says her daughter will start swimming lessons in the fall in preparation for many summers to come. Last year, her mother says, Tilly talked about the cottage all winter long. “The people who love the cottage most are Tilly and her Granny.”